The Effective Syllabus

Engaging students and communicating content.

What is an Effective Syllabus?

An effective syllabus is one that clearly outlines a student’s path to success in any course. The syllabus is often both the introduction to a course and its backbone, returned to continuously by instructors and students for guidance. The traditional syllabus has evolved from a short page describing the schedule and grading policy to a complete framework that helps students understand how to navigate your course successfully.

Many teachers think of the syllabus as a contract, and some even ask students to review and then sign the document to show that they have agreed to the terms. The syllabus can also be a map, designed to help students understand and navigate a course, or a set of FAQ’s, answering student questions. The syllabus can take many forms and almost always includes essential information for student success in the course. But to be effective as a student-facing document, the syllabus needs to present information in a way that is accessible to this diverse audience.

This can be challenging because students are not the only audience for a syllabus; oftentimes the syllabus is collected by departments/institutions and used as a means to review a course and/or teacher. As syllabus creators, we are pulled between multiple audiences and purposes and too often end up creating syllabi that meet all the explicit requirements, but fail to meet the student audience where they are. Your syllabus is one of the first communications you’ll have with your students. You have the opportunity to set a tone — make sure it is reflective of the relationship you hope to maintain with them.

How Can I Make My Syllabus More Effective?

Visual Design

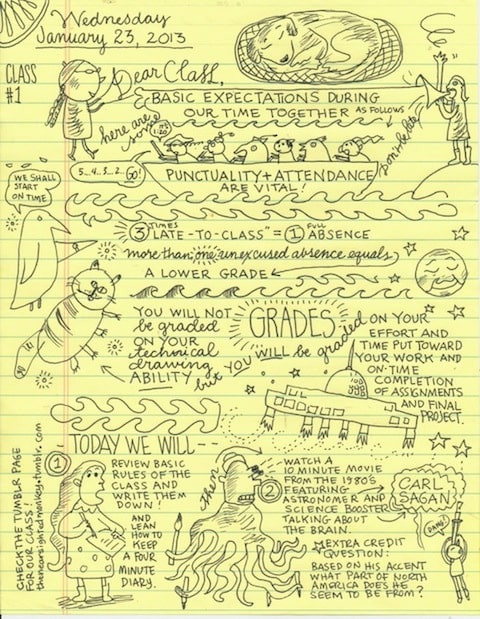

Use formatting (headings, columns) and images to help break up the sections of your syllabus; consider this example from UAF’s Sean McGee for his HSEM-121 course.

Inclusive Policies & Language

The tone of a syllabus is often rule-based and minimally forgiving; instead, write your policies the way you would in an email to a struggling student. In his presentation, “Toward Cruelty-free Syllabi,” Matthew Cheney asks, “What’s the tone of your syllabus? Do negative commands overwhelm positive invitations? Is the premise of the syllabus that students are untrustworthy? Are your policies designed to punish more than to support? Does the language reflect this?”

Break it down

In addition to centralizing all the important course information and policies in the syllabus, copy and paste these policies into relevant sections of the course. For example, when the first major assignment is due, you might remind students of the grading policy. You might post participation requirements at the top of the first discussion board, etc.

Additions for Online Courses:

Student Effort

The UAF Faculty Senate has determined that one credit hour [of non-laboratory instruction] represents “800 minutes of lecture (plus 1600 minutes of study),” which, for the standard 14-week semester, equates to a minimum of 1 hour of lecture (instruction) + 2 hours of study per credit hour.

Because we want all student activity to be meaningful, UAF CTL asks instructors to further document where student effort goes by percentage of effort into four categories that expand on the simple lecture/study ratio. These categories will demonstrate how the student will be spending their required time in the course. The four categories are:

- Instruction (minimum 33%: things like lectures, readings, teacher-student conferences)

- Individual Research (individual research for papers, projects)

- Assignments (actual projects and assessments)

- Collaboration (discussion, groups projects, blog commenting)

Example:

- Instruction: Lecture/Readings 35%

- Individual Research: Final project 10%

- Assignments: Quizzes, Homework, Blog posts 35%

- Collaboration: Discussion Board, Blog comments 20%

You may choose not to publish this information to your students, however, it is a necessary element to think about in the course development stage.

Submitting Assignments

Include guidelines for submitting assignments. What types of files are acceptable? Do you have file naming conventions? Should students submit on Canvas? Google Drive? A class blog? Be specific and be prepared to guide students through the submission process.

Response Time and Feedback

Clarify your policies on response time and feedback to students as part of your course policies. Set expectations for students by providing a specific window of time they can expect to hear back from you concerning email communications. Feedback on class assignments will likely be more time consuming, so clarify when you will be grading and when students should expect feedback on their coursework.

Technologies and Technology Support

If students are expected to use particular technologies in your course, provide links to where they can find those technologies. Include links to support services for these technologies when they are available. Outline any technical specifications for required software (Windows and Mac OS) or hardware.

If you are using 3rd-party tools in your course, provide links to support resources such as tutorials, accessibility information, and privacy policies.

In Practice

A syllabus is no good if no one’s reading it. Being specific, succinct, and organized are the first steps to readability, but design matters too. Check out the examples below for creatively designed and organized syllabi:

- Introduction to Homeland Security, UAF with Sean McGee — simple PDF that uses image and design for clear organization

- PR Writing, Marquette U — a syllabus as FAQs

- Northern Lit Syllabus, UAF with Madara Mason — a syllabus as infographic

- Web Graphics & Multimedia, UAF with Christen Booth — Clear policies regarding communication

- “The Unthinkable Mind,” UW-Madison with ‘¨Lynda Barry — hand-illustrated syllabus

- Chronicle of Higher Education list of Creative Syllabuses

- Chemistry Major’s Lab, Georgia College’¨ with Julia Metzker — a syllabus in the form of a Prezi

Technologies

There are a number of tools that you might use to build a dynamic syllabus, including:

- Prezi for an interactive presentation format

- Thinglink for creating an annotated, interactive image

- Pixton for making comics

- Pictochart for creating infographics

- Google Docs template for a “magazine-style” syllabus

Research Foundations

Barry, L. (2014). Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Instructor. Montreal, Quebec: Drawn & Quarterly.

Cheney, M. (2020). “Toward Cruelty-Free Syllabi.” Teaching in Higher Ed Podcast. February 13, 2020.

Slattery, J. M., & Carlson, J. F. (2005). Preparing an effective syllabus: Current best practices (PDF). College Teaching.