Decolonial & Indigenous Pedagogies

As a university, how do we build from acknowledging our presence on Indigenous land and start taking action? As educators, we have an opportunity to bring decolonial practices into our work through our classrooms.

Overview of Decoloniality

The form of colonialism practiced in North America is settler colonialism, which means that people from metropolitan countries take control of the land they colonize, with the intention of living on that land and staking claim to its resources in perpetuity, while changing the local culture and laws to suit their own values. Settlers claim this power is through violence and assimilation practices, what anthropologist Patrick Wolfe terms a “logic of elimination.”

In a settler colonial context, decoloniality is about recognizing that the settler’s seizure of land, resources, and power is harmful. For settlers, decoloniality means letting go of unearned privileges to land, culture, and power, and supporting Indigenous peoples in the reclamation of these rights.

Education has a significant role to play in decolonization. In the United States, formal academic settings have historically privileged (or violently imposed) white settler knowledge and ways of knowing. This education practice works to preserve settler power. As educators, we have the opportunity to disrupt this practice by integrating and valuing Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing in our classrooms. We can accomplish this both by including Indigenous perspectives within course concepts and readings and by creating a university culture that is welcoming to differences in experience and worldview.

It is important to remember, though, that a commitment to decoloniality asks for more than simple inclusion. Daniel Wildcat reminds us that the US education system is an “institution built on curriculum, methodologies,and pedagogy consistent with the Western worldview.” Decoloniality is an ongoing work that will require a fundamental restructuring of the academic environment.

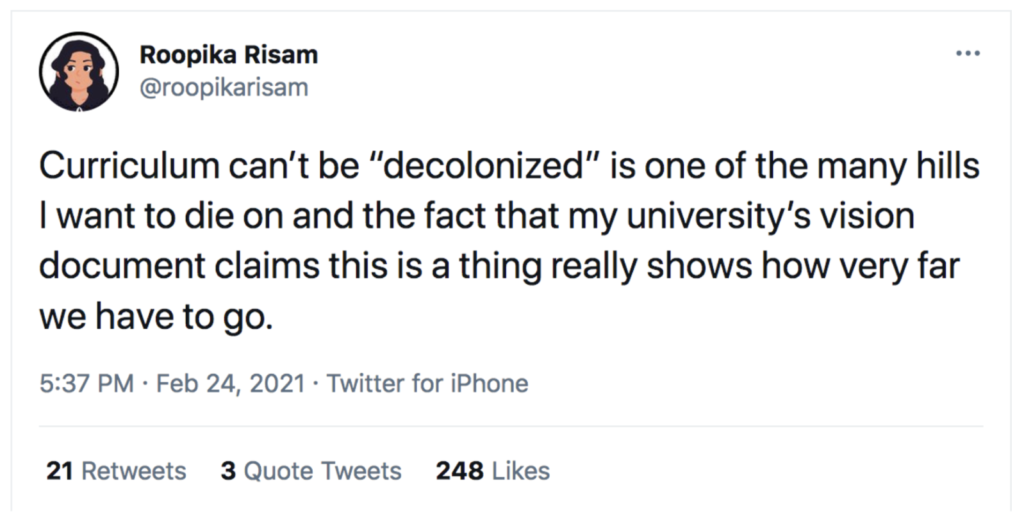

A Decolonized Curriculum?

Though the terms “decolonized curriculum” and “decolonized university” have become more common in recent years, many researchers of decoloniality have expressed concern that this language diminishes the real impact of decolonization.

Prominent decolonial researchers Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang ask educators to avoid using decolonization metaphorically, writing that “when metaphor invades decolonization, it kills the very possibility of decolonization” (p. 3). Likewise, Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Breeanne Matheson conclude that “overly broad uses of decolonial framework have the potential to remarginalize Indigenous peoples.”

Decolonization is about repatriating land and resources. Until that has happened, it is not accurate to use “decolonize” in the past tense when talking about our work in the university. As we seek to support decolonization with our curriculum, we ask: how can we use our classroom work to support the ultimate goal of relinquishing colonial power?

Action Steps

Stay grounded in the present

For those working on teaching within a decolonial framework, our mission is not only to repair past wrongs, but also to halt the land seizures, violence, assimilation efforts that are happening today. Learn about contested land and resources near you today, as well as contemporary reclamation efforts. Avoid framing colonization and Indigenous life in the past.

Acknowledge the role of the university and education in colonization

The work of the university has been a major contributor to colonization, through land claims, unethical research, and assimilative education tactics. Decolonial work in a university is difficult because we are working against our own structure. You might think of it like trying to dig up the foundation of a house that we are still living in.There are going to be challenges! At the same time, our embeddedness opens up opportunities to make real change. Give yourself some time to reflect and imagine: what could a decolonial future look like at the university?

Commit to the other “D” words

So what do we do when we want to support decolonial goals, but know that we are not (or not yet) directly working towards land return? Appleton suggests focusing on other “D” words, like those named in the pullquote here.

Explore Indigenous perspectives in/of your field, and engage students in those perspectives. How might a decolonial lens help you and your students reimagine your subject of study? You can find a short list of (mostly STEM) texts to get started with here.

Let go of quick fixes

Decolonization will not happen overnight, neither will cultivating decolonial practices in our classrooms. Working with urgency leads us to make less significant, sometimes harmful, and usually short-term changes. Remember that this is a continuous practice.

Learn as you teach

Appleton asks non-Indignenous instructors to “Take the extra time to learn how we think, read, and write. Learn from us the ways we see and seek to change this oppressive world. Respect our refusal to write like you, even after you train us well to write like you.” Consider how you can position yourself as a learner in your own classroom. How might you open up space in your course policies to learn from your students? What policies may help you engage with student refusal?

“Diversify your syllabus and curriculum

Digress from the cannon

Decentre knowledge and knowledge production”

Decentering Whiteness in Antiracism Initiatives with Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq

References

CLEAR, “Decolonizing your syllabus? You might have missed some steps”

Deloria and Wildcat, Power and Place: Indian Education in America.

Memorial University, Indigenization is Indigenous

Itchuaqiyaq and Matheson, “Decolonizing Decoloniality: Considering the (Mis)use of Decolonial Frameworks in TPC Scholarship”

la paperson, “Land. And the University Is Settler Colonial” in “A Third University Is Possible”

Nash “The dark history of land-grant universities”

Pember, “The Traumatic Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools”

Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor” (PDF)Wolfe, “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native”

Additional Resources

8 competencies for culturally responsive teaching

Alaska Native-themed Requirements – University of Alaska Fairbanks

Alignment to Multicultural Education, Diversity, and Equity

Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally Responsive & Inclusive Curriculum Resources: Creating Culturally Responsive Curriculum

Colorado Culturally Responsive Instruction Resource List

Culturally Responsive Curriculum Scorecard

Culturally Responsive Curriculum

The First Peoples Principles of Learning: An Opportunity for Settler Teacher Self-Inquiry

Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education: Mapping the Long View

More Holistic Assessment For Improved Education Outcomes (PDF)

Respect Relationships Reconciliation (3Rs) Study Course

Value-Creating Perspectives and an Intercultural Approach to Curriculum for Global Citizenship