Learning Taxonomies

What is It?

Most of us agree that our purpose as instructors is to foster or facilitate new student knowledge. How best do we measure a students’ grasp of course content or core ideas. There are levels to knowledge from the simple, remembering one’s times’ tables, to extremely complicated, knowing about oneself. Scholars have tried to create taxonomies of understandings or taxonomies of educational goals. Perhaps the most well-known is Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive domain (1956) later revised by Anderson (2001). This taxonomy features a hierarchy of categories to capture the range of learning processes: Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, Create. Anderson extended these categories with the addition of a knowledge dimension: Factual, Conceptual, Procedural, Metacognitive.

Similarly, Wiggins and McTighe developed Six Facets of Understanding (1998) to help educators design deep or varied learning experiences. This encourages us to build learning experiences to develop more than superficial or imbalanced understanding without including solid foundational knowledge.

| Six Facets | Description | Example |

| Explanation | To ensure students understand why an answer or approach is the right one. Students explain or justify their responses or their course of action. | Students develop an illustrated brochure to explain the principles of a type of technology (i.e., transportation, construction, medical, information). |

| Interpretation | To ensure students understand why an answer or approach is the right one. Students explain or justify their responses or their course of action. | Students develop a ‘biography’ of the development of a particular type of technology. |

| Application | To ensure students’ key performances are conscious and explicit reflection, self-assessment, and self-adjustment, with reasoning made evident. Authentic assessment requires a real or simulated audience, purpose, setting, and options for personalizing the work, realistic constraints, and “background noise.” | Students analyze a design of a product, taking it apart in order to determine how it works. Students design, develop, test, and revise a solution to a local issue, such as a new roadway system, a water treatment system, or long-term storage of various materials. |

| Perspective | To ensure students know the importance or significance of an idea and to group its importance or unimportance. Encourage students to step back and ask, “What of it?” “Of what value is this knowledge?” “How important is this idea?” “What does this idea enable us to do that is important?” | Students investigate a technological artifact from the perspective of different regions and countries. |

| Empathy | To ensure students develop the ability to see the world from different viewpoints in order to understand the diversity of thought and feeling in the world. | Students imagine they are politicians debating the value of nuclear power. They write their thoughts and feelings explaining why they agree or disagree with the use of nuclear power. |

| Self-Knowledge | To ensure students are deeply aware of the boundaries of their own and others’ understanding: able to recognize their own prejudices and projections; has integrity —able and willing to act on what one understands. | Students reflect on their own progress of understanding one of the standards in Standards for Technological Literacy: Content for the Study of Technology. They evaluate the extent to which they have improved, what task or assignment was the most challenging and why, and which project or products of work they are most proud of and why. |

Source: Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998) Understanding by Design. p. 95-97. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Examples reworded for brevity.

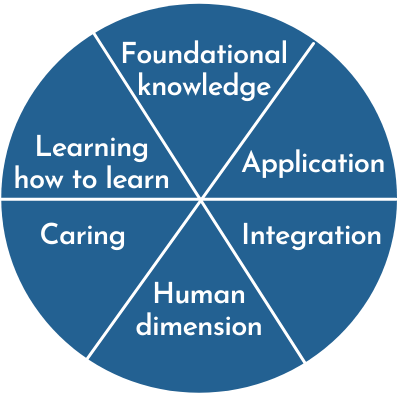

Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning (2003) challenged the hierarchical nature of previous models and presented a more holistic taxonomy including the ‘Human Dimension’ and ‘Caring: Developing new feelings’. Many instructors hope their students become better at learning how to learn and become self-directed learners but few identify these specific goals and fewer still design to achieve them. It is interesting that much of the traditional classroom experience fits within the single ‘Foundational Knowledge’ sector of the model.

Taxonomy of Significant Learning

Six Segments

- Foundational Knowledge—

Understanding and remembering:

information, ideas - Application—Managing Projects; Skills; Thinking: critical, creative, practical

- Integration—Connecting: Ideas, People, Realms of life

- Human Dimension—Learning about: Oneself, Others

- Caring—Developing new: Feelings, Interests, Values

- Learning How to Learn—Becoming a better student; Inquiring about a subject; Self-directing learners

How Can I Use Learning Taxonomies in My Course?

There are several ways learning taxonomies may be valuable. The first is just to recognize that understandings are complicated and diverse. There are superficial understandings and deeper, more profound understandings. Ask yourself what kind of understandings you’d like your students to achieve. If you’ve been teaching your course for a while, consider your existing activities. Some find the process of diagraming their course learning activities or outcomes and their corresponding taxonomic categories helpful. Does your course feature mostly one type, or a diversity of types?

Further, and very importantly, there are often multiple ways to achieve similar understandings. For instance, if you want students to empathize with characters or figures, there are multiple ways to achieve that objective. You could have your students write a diary in the voice of that persona, or play an immersive role-playing game, perform a skit or deliver a presentation as that person or debate as that person. Once you clearly identify your intended objective, you can consider a wider and often more engaging range of activities to achieve that same objective.

Learning taxonomies may resonate with you or they may not. Try not to be put off by the jargon or the coarse categorization of the complex and largely unknown nature of human understanding. They can be very useful tools during the course design and learning experience evaluation process. Use what strengths they afford, and look for better solutions where they fail to apply.

Questions and Considerations

What do you want your students to know? How do you want them to be able to demonstrate this knowledge? Are you designing for rich outcomes and deep understandings?

There are more learning taxonomies including adaptations and remixes of those listed here. Mix and match elements that resonate with your experiences as a student and as an educator. Use them as a tool to analyze your existing activities, and to inform your design for future activities.

Favorite resource

Use a subset of Bloom’s Taxonomy to start your objectives with a measurable verb.

Idea Box

- Locating and storing domain knowledge

- have students create a Google Drive folder containing pdfs, images and videos

- have them share the folder with you for evaluation and feedback on the quality of the items that were collected.

- Thinking critically about the existing body of knowledge and any newly gathered data by generating a mind map of how various concepts are linked together, creating a taxonomic map. Additionally, students can engage in the critical thinking process in well-constructed discussion boards.

Research Foundations

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airiasian, W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., & Pintrich, P. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational outcomes: Complete edition. New York, NY: Pearson.

Bloom, B. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals – Handbook I: Cognitive Domain (2nd ed.). New York: David McKay Company, Inc.

Fink, D.L. (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., and Masia, B.B. (1964). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook II: Affective Domain. New York: David McKay Co.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by Design. Alexandra, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.