Proactive Measures to Help Students with Post-COVID Mental Health Issues

The first hint I got that something was different about students with disabilities at UAF this year was in a casual conversation in September about semester start hustle with Marissa Jesser, the Assistant Director of Disability Services, when she said something along the lines of “We’re swamped – there are 33% more students registered with Disability Services than there were last year.” The hustle didn’t let up at the Disability Services office – by the end of Fall, there were almost 400 students with a declared disability registered and receiving accommodations.

Maybe it’s something you’ve felt as an instructor this year, or gathered anecdotally as in-person students have been returning. The COVID-19 pandemic has subsided, but the tone around living with disability and mental health issues at college has changed. What exactly has happened, and why? Does it affect how you teach, and how you engage with students?

This article will dig into national student health data to see what’s changed numerically between 2019 and 2023. Then, with help from the Director of Disability Services, Amber Cagwin, and Marissa, we will explore some of the reasons behind these changes and how it has manifested here at UAF. Finally, I’ll offer some tips on building more accessibility into your classes and working productively with students with disabilities.

Takeaways

- Compared to Fall 2019, significantly more students are dealing with mental health issues now, both nationally and at UAF.

- The social disruptions of the pandemic also impacted the development of the executive function and self-advocacy skills needed to navigate higher education with a disability.

- Adaptation is necessary because these changes are not going away anytime soon.

What happened between Fall 2019 and Spring 2023?

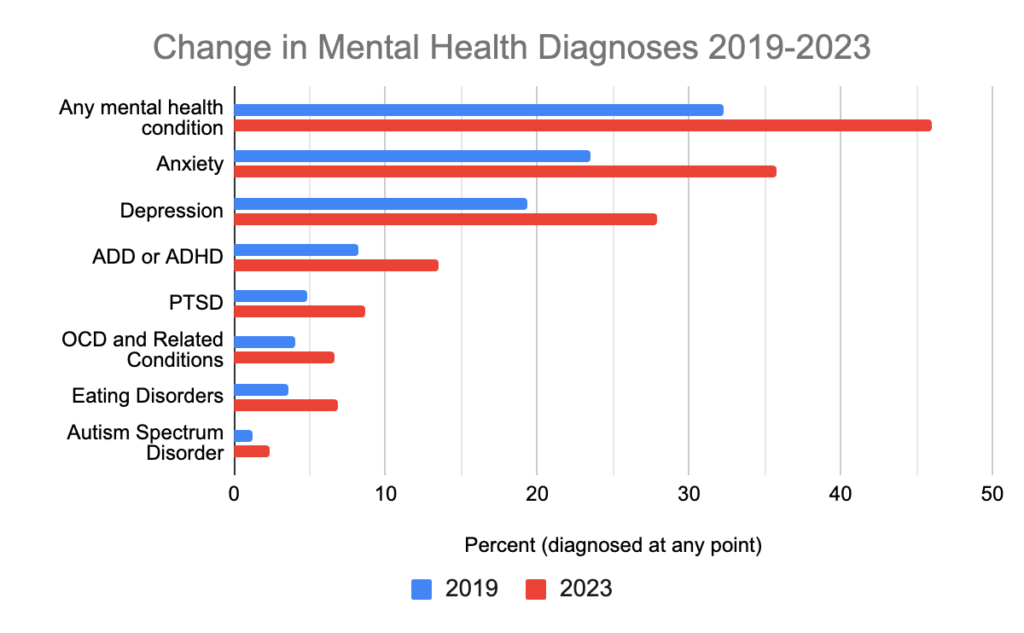

The American College Health Association [1] administers the National College Health Assessment each semester to participating public and private universities across the U.S. This is an incredible dataset – in Spring 2023 there were 78,024 respondents from 125 schools. The survey instrument was the same between Fall 2019 and Spring 2023 (the most recent available report), so it’s possible to do a direct comparison.

The change is most striking in the section about mental health. Rates of anxiety and depression have soared, and diagnosis of other mental illnesses have also increased 60-100% since 2019. The chart above reflects “diagnosis at any point in life” but more students are actively receiving treatment. 38.4% of students in Spring 2023 received psychological or mental health services within the last 12 months, compared to 26.0% in Fall 2019. (Note: Autism Spectrum Disorder is included on this list, but it’s important to note that many people with autism consider their diagnosis not as a “mental health issue,” but as a valuable part of their identity.)

There has been a downward trend in physical health among college students. 29.8% of students in Spring 2023 reported that their academic performance has been negatively impacted by “any ongoing or chronic medical conditions diagnosed or treated in the last 12 months, compared to 22.0% in 2019. Permanent physical or intellectual disabilities affect a relatively small proportion of college students, making it difficult to assess the statistical significance of the increases reported.

The survey also has a whole set of questions about life circumstances that have negatively impacted academic performance and there is a steady increase in incidence in the majority of these categories. This includes things like financial trouble, conflict with a partner, death of a loved one, and difficulty with a faculty member.

Understanding Changes Nationally and at UAF

I sat down with Amber and Marissa to talk about this data and gather their thoughts on the reasons behind it and how it has manifested at UAF. When I asked about the surge in mental health issues, they see the social and economic upheaval of the pandemic as a catalyst that has created more mental health problems, but also brought to the surface many things that previously went unacknowledged. Amber stated, succinctly, “This is not going to go away.”

Marissa has a term for what’s happened. “It’s all about the theory of Allostatic Load – the idea that prolonged stress can damage the body and the mind [2]. We all deal with stress throughout our lives, and everyone has different thresholds for when that stress becomes unmanageable and they begin to experience mental or physical health issues. It is something that can ebb and flow based on the person’s circumstances, but prolonged experiences of stress – being stuck in that “fight or flight” mode – can be debilitating. The cumulative stressors of the pandemic tipped a lot of people over the edge in the past few years. You can assume that at least 40-50% of your students aren’t doing as well mentally as they were in 2019.”

Leaving that long-term stress behind has not been easy for many students, even as pandemic restrictions ease. The recession that started during the pandemic is still in full swing and young adults are impacted acutely by it. Wages and financial aid have not kept pace with the increasing cost of housing, transportation, and food – things that were already expensive in Fairbanks prior to the pandemic. Remember the iconic triangle of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – if base needs are not met, mental recovery is very difficult.

Social-emotional impacts of the pandemic

When students with disabilities enter college they transition from receiving federally-mandated, responsive support in K-12 (via an IEP [Individual Education Plan]), to a world where academic accommodations rely entirely on their own proactive effort and self-advocacy. The effects of the pandemic have not made this transition easier.

Amber and Marissa have seen much higher levels of social anxiety in their office – both as officially diagnosed agoraphobia, and concurrent social concern with other disabilities. Initiating communication with instructors is difficult for these students, as is interpreting tone, both in person and via email. Students are more likely to not reach out until they hit a point of crisis, and they may also lack the skills to work productively with an instructor to negotiate an accommodation.

The social disruptions of the pandemic also impacted the development of the executive function skills that are vital to being a successful college student. Trouble with executive function and mental health often go hand-in-hand and can lead to a downward-spiraling feedback loop. According to Marissa, “Common symptoms of depression and anxiety such as procrastination, avoidance of stressors, worry, and lack of motivation have gradually become more prevalent or severe during pandemic. This means some people don’t know that they are impaired and could benefit from additional support.”

On the upside, talking about mental illness is less stigmatized by Gen Z. There is broader public consciousness and sense of identity among younger people who have mental illnesses – how they are learning to advocate for themselves has changed [3]. There is also an increased awareness of the history of gender bias in psychiatry. Medical practitioners have gained a better understanding of how Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD present in females, which may be a factor in the increase in diagnosis.

Physical Disabilities… And their cognitive impacts

I was curious if Disability Services has seen any changes in the number of students with physical disabilities who are receiving services. Amber told me that about 2% of students served by their office this year officially have Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. As a new type of auto-immune disease, it can be incredibly hard to diagnose, meaning many have an alternate diagnosis or go undiagnosed. She said that accommodations for Long COVID are often similar to post-concussion and learning disabilities.

Long Covid, like most common physical disabilities, is invisible. Disability Services works with a number of students with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), a circulation disorder that can cause rapid heartbeat or fainting when someone stands up too quickly.

They also work with students who have genetic disorders like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, which causes joint issues that can lead to frequent dislocations and early-onset arthritis. These are just two examples of conditions that are chronic, variable, and usually invisible to others unless the student chooses to disclose their disability status.

Marissa and Amber both noted that living with a physical disability often goes hand-in-hand with psychological distress (because, hey, it’s tough to navigate the world with a disability!) and that psychological distress is often the barrier to academic success. Changes and inconveniences that able-bodied people find inconsequential can pose much bigger problems for people with physical disabilities. Having to disclose difficulties and negotiate for accommodations can be enormously stressful, especially when a student is uncertain how receptive an instructor will be.

Adapting to Student Needs

So, if all of this is not going to go away, what does adaptation look like?

I know instructors already have been grappling with adapting their teaching to new realities since Spring 2020 when the pandemic caused a massive shift to online learning. Many instructors I know started looking into topics like trauma-informed pedagogy as they struggled to connect with students whose lives were in upheaval. I have been deeply impressed and inspired by instructors who have made major changes in their course design and teaching style – guided by both empathy and an unwavering belief in the capabilities of their students.

The recommendations I got from Disability Services mirrored my own research: a good approach to make your course a better experience for students with any disability is founded in clarity, communication, and flexibility.

Clarity

Help students understand exactly what they’re signing up for before the add-drop deadline, or even before the start of the semester. (Watch for a Teaching Tip this summer on creating a public course site or Canvas page that students can look at before enrolling!) Publish thorough information about major assignments and course expectations:

- Is there required group work or public speaking?

- Are there field trips or meet-ups at a different time or place than in the course listing?

- Is your syllabus late policy actually accurate to how you handle late work?

- Is your gradebook set up so students can accurately track their course grade?

Communication

One way to signal that you are dedicated to working productively with students with disabilities is to personalize your Disability Services syllabus statement and highlight it in your course welcome materials. (This resource from Explore Access has interesting examples.) Framing disability accommodation as solely a matter of legal obligation can set an adversarial tone. Instead, acknowledge that, if your course presents barriers, you are part of the team (along with the student and DS) to figure out equivalent accommodations that truly help the student. Remember that students themselves are often still in the process of understanding their disability and figuring out how to self-advocate effectively.

A policy I started seeing more frequently during the pandemic was allowing for one or two no-excuse-needed extensions or absences. Instructors don’t enjoy receiving extension requests with distressing multi-paragraph explanations full of personal details and students really don’t enjoy writing them. Feeling obliged to disclose private information in order to provide a “valid” excuse is stressful, demeaning, and can discourage some students from communicating with a professor at all. Even without a policy like this, taking students at their word and not requiring detailed justification will more often benefit a student who needs it than enable a student who doesn’t, and it will help establish a relationship of mutual respect in your classroom.

Flexibility

Building flexibility into all aspects of your course goes beyond granting extensions. It requires you to think deeply about the core skills and understandings students should take away from your course. Which requirements are essential, and which are window dressing? For example, a science course requires a 10-minute presentation for one of the final assignments. Is the core skill public speaking, or is it the ability to summarize original research? You can ask similar questions about test formats, discussion requirements, etc.

There is not always a cut-and-dry answer to these questions so the federal laws governing academic accommodations in higher education account for this as follows:

“Educators must make necessary modifications to the academic requirements of a course of study if these requirements have a discriminatory impact on a student with a disability. Educators, however, do not have to waive or change the requirements if they are essential to the course or if the changes would fundamentally alter the program.” [4]

Academic accommodations are defined as an “interactive” process, meaning that you are part of the team that decides what appropriate accommodations look like. Taking a critical look at the purpose of your course can help you think flexibly when the need for an alteration arises. Better yet, you can incorporate some of that flexibility into assignments proactively, which eliminates the need for individual accommodations and creates options that can benefit all students.

References

[2] https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-allostatic-load-5680283

[3] https://www.verywellmind.com/why-gen-z-is-more-open-to-talking-about-their-mental-health-5104730

Great article, Clara! I really appreciated the insight about the spike in disability service registrations—it’s eye-opening to see how the pandemic’s long-term effects are playing out in higher education.

One thing that really stood out to me was your mention of allostatic load. It got me thinking: have you noticed specific teaching strategies or accommodations that seem to help students better manage this ongoing stress? I’m curious if you’ve seen anything particularly effective for supporting students’ mental health while still maintaining academic standards. Would love to hear your thoughts!