Learner-Generated Drawing Holds Potential for both Learning and Assessment

This teaching tip has two main components. The first is a brief survey of recent peer reviewed journal articles on learner-generated drawing as the basis for learning activities and assessments. The second is reflections and conversational highlights from University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Don Larson and Shayla Sackinger, who share faculty and student perspectives on creative exercises in general and illustration activities in particular.

In order to avoid imprecise vocabulary use, the phrase ‘learner-generated drawings’ will use the working definition from van Meter and Garner’s 2005 The promise and practice of learner-generated drawing. These authors distinguish between clearly labeled drawings that illustrate a complex structure or spatial representation from works that incorporate more artistic styles such as those found in impressionistic, cubist, or surreal styles. Further, the authors define learner-generated drawings as having three qualities: They are created intentionally to meet an educational goal; they are meant to represent subjects accurately; and the learner is responsible for the development and final appearance.

This subject began to generate research articles in the 1970s, but the results were mixed, and the field became less popular until about 2005 when researchers focused on a more narrowly defined idea of what a learner-generated drawing was, and the quality upon which it was generated.

Researchers did start noticing that there was a strong correlation between accurately produced illustrations by students and later memory retention and performance on more typical assessments. Although the question of why this occurs was partially addressed by earlier efforts, the authors of The drawing effect: Evidence for reliable and robust memory benefits in free recall conducted careful research with a variety of factors on student drawing as a learning activity. They concluded that “the process of drawing a verbal item engages at least four components.” Their argument was that in order to transfer something from spoken or written word into imagery, the student must first engage in an elaborative effort, representing physical characteristics of a subject visually. In doing this the student must employ hand and eye movements to draw something. The result is that an image is created, not only on paper, but in the student’s mind [2].

Takeaways

- Learner-generated drawing is similar to summarization, self-questioning or prior knowledge activation. The behavior of producing a drawing is believed to direct cognitive processes responsible for task performance [1].

- Learners may need prompts and examples, especially if they have little experience with creating illustrations

- Student created illustrations can optionally be shared with the public via work portfolios, such as the one associated with UAF’s Human Anatomy and Physiology course at: humanap.community.uaf.edu. This practice can benefit students in future semesters.

Do all drawing efforts have equal benefits for memory and later assessment performance? Not exactly. Although asking students to sketch things during a lecture, or during periodic breaks after reading text does engage various cognitive and metacognitive processes which are beneficial to learning, these effects begin to diminish when the drawing activity itself becomes a “highly demanding cognitive task” [3].

In other words, if a student needs to concentrate to a large degree on the process of drawing itself and perhaps doesn’t have much in the way of what we’d consider artistic ability, the positive effects of memory retention and comprehension are somewhat diminished. The good news is that the same study offered advice to provide all students with support to lessen the reluctance to generate a drawing by providing a drawing prompt. The authors urge that prompts be provided to students so that they can minimize their need to focus on the mechanics of drawing. Such prompts could be examples of other helpful sketches or the beginning stages of a completed drawing.

The same article, Drawing as a generative activity and drawing as a prognostic activity, made the point that by examining the quality of student drawings, the instructor could ascertain in a formative way, any possible shortcomings in student comprehension of a particular subject.

Shayla Sackinger, an instructional designer specializing in illustration at the Center for Teaching and Learning, offers similar advice for faculty. She urges instructors to periodically assess students’ level of understanding during the teaching of a course. She outlines benefits to using illustrations in class and some strategies to do so efficiently.

Benefits

- Critical Thinking: Illustrations encourage students to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information, fostering deeper understanding and innovation.

- Problem-Solving Skills: Creative tasks often present unique challenges, helping students develop flexible thinking and adaptability.

- Self-Expression: Such assignments allow students to express their individuality and personal perspectives, enhancing engagement and motivation.

- Collaboration: Many creative projects involve teamwork, promoting communication skills and the ability to work well with others.

- Interdisciplinary Learning: Creative assignments often integrate knowledge from various fields, encouraging a broader perspective and holistic understanding of subjects.

- Preparation for Real-World Challenges: They simulate real-world problems where creative solutions are often required, preparing students for future careers.

Strategies

Providing a creative assignment for your students isn’t difficult if you set some firm guidelines beforehand.

- Let your students know about the creative assignment ahead of time. Put it in the syllabus!

- Clearly define what is allowed and not allowed. How much work is expected of this project?

- Provide examples of what is expected! Or describe it best you can if this is the first time trying an assignment like this.

- Make a grading rubric so it is easy for students to understand how you will be grading this assignment. It will also help you grade faster.

- Don’t forget to have fun and enjoy seeing what your students create. They will surprise you!

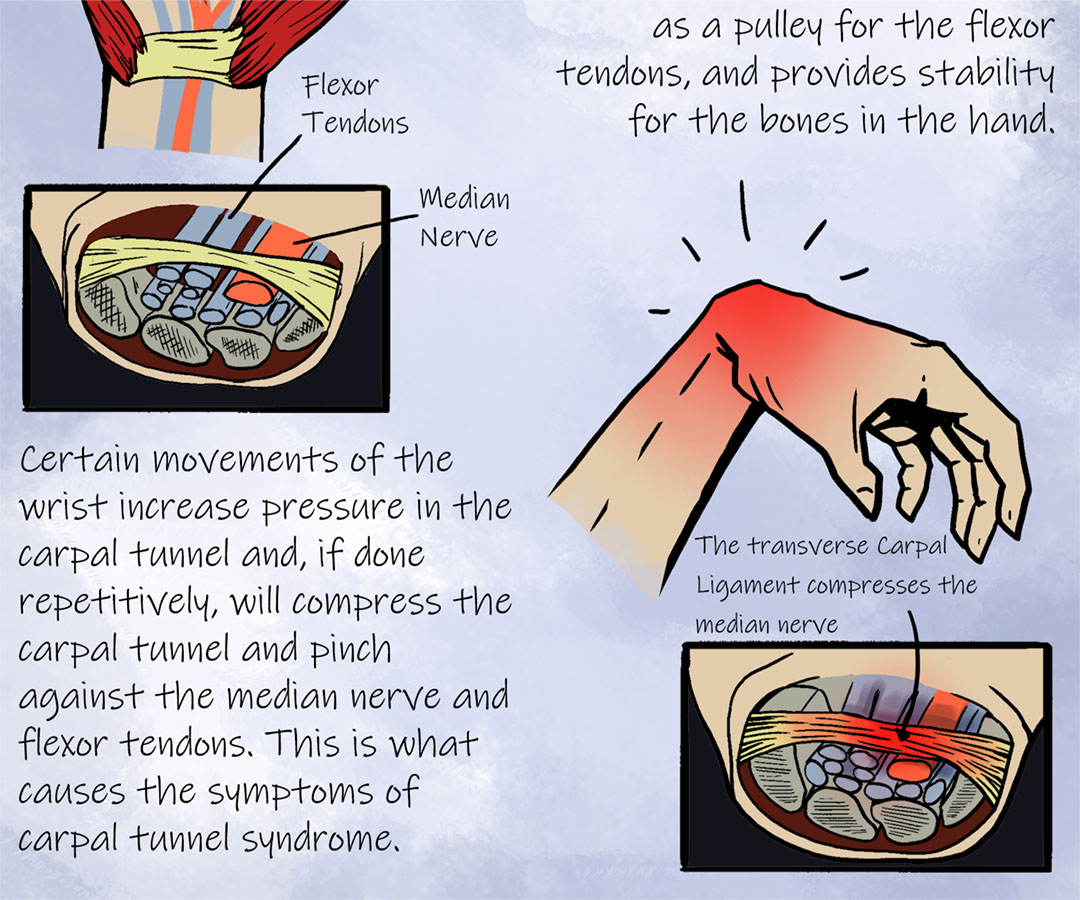

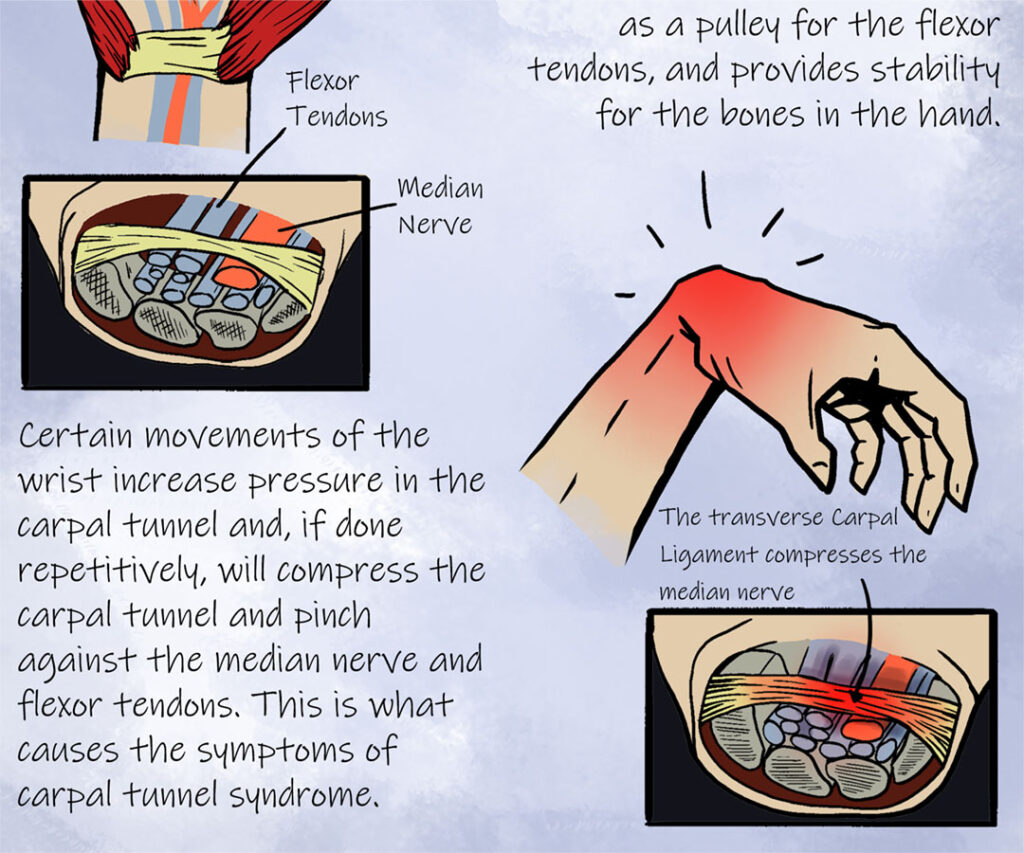

Sackinger’s undergraduate study at UAF included a Human Anatomy course from Don Larson. One of the larger projects in the class included a large creative project. She had the opportunity to use her love of comics and illustration to convey what she had learned about Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. The STEAM project archive can be viewed on the humanap.community.uaf.edu site.

In researching this topic, Sackinger had the opportunity to ask Don Larson about his thoughts regarding the creative project in the Anatomy class. Their conversation follows:

How did you come upon using this kind of assessment in your class?

I was looking for an alternative to lab practicals in my online course. I decided to use a project instead of an exam for my summative assessment. I realized that reading 200+ essays in a 100-level class would not be ideal. That’s when I began creating an art-based project. I wanted students to communicate what they learned in my course and art was a great way to do that. I have now included multiple art activities and art-based assessments in my courses.

How long does it take to provide feedback versus more typical assignments?

I have found that art-based projects do not take longer to grade than other projects. Designing a useful rubric was the main time sink for using art-based projects in my courses. With a good rubric grading is faster than grading some exams.

How do creative assignments compare with other assessments in terms of providing you an insight into a student’s competencies?

I have used art-based projects primarily as a tool for science communication. This process results in a few insights into students that traditional exams and essays may miss. First, students have to work through the big picture instead of details with an art project. They have to simplify complex physiology into something that can be conveyed in an image, movement, or sound. Sometimes the easier part is memorizing that biochemical pathway and the hard part is explaining why it is important. Art projects allow students to focus on the latter.

I have had success emphasizing that, with an assessment in BIOL 310 Animal Physiology, in which students created a children’s book. They quickly learned that trying to distill what they learned into simple sentences and images is quite hard, but also very useful for getting the big picture. Second, art-based projects let students show me skills that I would not know they have using traditional exams and essays. Our students are incredibly talented but we sometimes limit them unintentionally by using a limited framework to assess them. Every semester there are projects that I learn from and projects that amaze me. Third, using art-based projects helps build student confidence and competency in course work that traditional exams and essays don’t, as art-based assessments are effort based.

I see students that do poorly on exams showing me a thorough understanding in a way they can’t on those traditional assessments. I see them learning when that’s not always clear in my traditional assessments. Art-based projects help students develop communication skills, use skills they traditionally wouldn’t in a science course, and demonstrate competency in an alternative way.

What is your advice to other instructors who might be contemplating the use of creative assignments as a learning activity/assessment?

Sprinkle in an art-based project or two in your course. Explain to your students why you are doing it and what you hope to accomplish. An activity here and there can make a big difference. You don’t need to upend your whole course. Also, you do not need to be a capable artist to do art-integrative lessons and activities. I have avoided art classes since I was in middle school. I have always been that very science focused student, but I recognize how useful art is for students.

How do you handle the situation of asking students to make/draw something, when they don’t see themselves as artists?

I approach engagement and buy-in for art activities in multiple ways. First, I explain why we are using art in my courses. I use examples of how scientists have used art in the past. I discuss how art can help communicate their knowledge. I explain how art can help them understand the material better. Second, I lean on my Course Assistants (CAs) to explain the usefulness of these activities. All of my CAs have taken my course. Hearing from a peer, especially a peer they identify with, on the benefits from art activities increases engagement. Finally, I set an achievable standard for art projects. That standard is that they need to be a better artist than me, a very low bar. I use a story about painting with my son (5 at the time) and how my wife was genuinely uncertain as to whom completed which piece. This also helps students focus on process over product which has become a point of emphasis in my courses.

Conclusion

Many of the points that come forward after reading the relevant literature are also evident in the conversation between Sackinger and Larson. Incorporating drawing exercises in your class can provide your students with a variety of ways to demonstrate their understanding of course material. As Larson points out, he was able to see evidence of learning and competency in areas that went beyond the traditional exams, quizzes and homework.

References

[1] Van Meter, P., & Garner, J. (2005). The promise and practice of learner-generated drawing: Literature review and synthesis. Educational psychology review, 17, 285-325.

[2] Wammes, J. D., Meade, M. E., & Fernandes, M. A. (2016). The drawing effect: Evidence for reliable and robust memory benefits in free recall. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(9), 1752-1776.

[3] Schwamborn, A., Mayer, R. E., Thillmann, H., Leopold, C., & Leutner, D. (2010). Drawing as a generative activity and drawing as a prognostic activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 872.