Using Student Feedback to Improve Teaching

“Are students getting anything from my lectures?” It’s an early morning class with about 40 students, and the instructor is wondering why they are getting a lot of blank looks and silence whenever they ask if anyone has questions.

I jot down the instructor’s question as I prepare to attend their class to run a Mid-Semester Feedback session. On the day of the session, the instructor introduces me and leaves the room 45 minutes before the end of the period. After explaining the purpose of my visit, we begin the three-part feedback gathering process. First, there’s a few minutes of quiet, concentrated scribbling as students write individual responses to the prompts. Then they gather in small groups to discuss and a constant buzz of on-topic conversation fills the room. Finally, students share statements that they developed in their small groups, and the whole class votes.

Here’s an example of what the students generate in relation to the instructor’s questions about the lecture portion of the class. (These examples are not from a single class, but paraphrased from several Mid-Semester Feedback sessions over the past two semesters.)

Takeaways

- The Mid-Semester Feedback program at UAF is based on Small Group Instructional Diagnosis (SGID), a method for gathering student feedback that has been used at hundreds of universities over the past 45 years.

- Mid-Semester Feedback provides an opportunity for formative assessment of teaching, gathering different responses than traditional end-of-semester evaluations.

- Students feel positively about instructors who do mid-semester feedback.

- Interested in participating? Register for Fall 2025!

1. What is one thing you would like the instructor to start doing in this class that would help you learn?

| Statement | Agree | Disagree | Neutral |

| More signposting in slides – emphasize important points and show more clearly when switching from one topic to the next | 36 | 0 | 4 |

| More breaks in class for small group discussion/interactive activities/polls | 24 | 8 | 6 |

| Provide lecture outline or slides or something else before class for guided notetaking | 32 | 2 | 6 |

2. What is one thing you would like the instructor to stop doing in this class that isn’t helping you learn?

| Statement | Agree | Disagree | Neutral |

| Sometimes the text on slides is too much/too small | 30 | 0 | 10 |

| Moving through class time quickly, moving on too fast from questions | 21 | 10 | 9 |

3. What is one thing you would like the instructor to continue doing in this class that is helping you learn?

| Statement | Agree | Disagree | Neutral |

| Instructor is obviously passionate about the subject and shares fun/cool examples | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Posting slides after class is helpful | 36 | 0 | 4 |

| The polling tool gives a good break from just listening during lectures | 28 | 7 | 5 |

Origins of Mid-Semester Feedback

Like the example instructor above, anyone who has ever lectured before has had moments where the silence stretched a little too long and they wished they knew what students were thinking. The same is true for every other aspect of teaching as well. Everything we do as instructors is for the benefit of students, but it’s famously difficult to get a straight answer from students about how well we’re doing.

I’ve been fascinated with the potential for student feedback since 2021, when I was involved in launching LEAP, a student pedagogical partnership program for online classes. As on-campus classes filled again after the pandemic, I figured the time was right for a student feedback program for in-person instructors. Thankfully, an excellent model already existed.

The process used for the Mid-Semester Feedback program at UAF is based on the Small Group Instructional Diagnosis (SGID) evaluation technique developed at the University of Washington in 1979 [1]. The idea that input from students can play a role in improving (or at least evaluating) teaching at the university level has been around for longer, but the innovations of SGID were created in response to some fairly obvious observations:

- Feedback in the middle of the semester allows the instructor to make adjustments for that semesters’ students.

- Students conversing in small groups will generate different things to say about the course compared to individual written feedback.

- Involving a trained facilitator to gather feedback from students and then interpret it with the instructor will improve both feedback and outcomes.

This reasoning made sense to a lot of people, and it didn’t take much time or resources to implement, so adaptations of SGID have been used at hundreds of universities in the United States and around the world since the 1980s.

As I developed the version we use here at UAF, I spoke with professionals at several other universities who run similar programs. In some places it’s mandated for faculty, or highly incentivized, while other institutions keep it as an optional piece of faculty development. Some programs are run by staff at Centers of Teaching and Learning, while others use peer faculty as facilitators. The feedback-gathering tools vary significantly, as does the time commitment for faculty. I adapted the question set for students from a program at Western Michigan University [2] and borrowed the three-step feedback gathering process from Northern Iowa University. This three-step process takes 40-50 minutes of in-class time, while some other programs wrap up sessions in 30 minutes or less, but I believe the quality of feedback gathered through this method is worth the time invested. Jonathan Chenoweth, the Director of NIU’s Center for Excellence in Teaching & Learning, also provided great advice on training others to act as program facilitators, and UAF’s Facilitation Guide is adapted from his program as well.

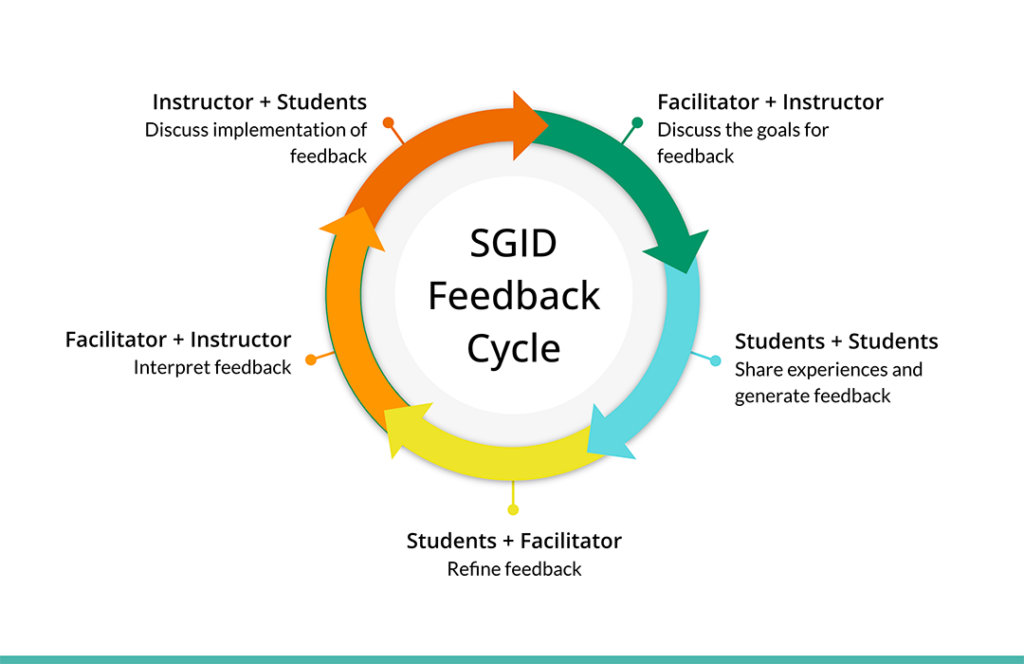

The program facilitators I spoke with, and the many articles I read, all emphasized that the value of this process lies in the way it structures feedback as a closed-loop circle of interactions. A SGID-based program generally follows the following set of interactions:

- Facilitator + Instructor: Discuss the goals for feedback

- Students + Students: Share experiences and generate feedback

- Students + Facilitator: Refine feedback

- Facilitator + Instructor: Interpret feedback

- Instructor + Students: Discuss implementation of feedback

The power of a SGID-based program lies in this cycle of conversations. The authors of the 2022 book Midcourse Correction for the College Classroom: Putting Small Group Instructional Diagnosis to Work put it into words nicely:

“Each SGID conversation holds a promise to make teaching and learning a more transparent, collaborative, and meaningful experience. Although students often talk with other students, and instructors most certainly talk with other instructors, the SGID conversations provide a space for these players to talk openly and purposefully about teaching and learning.” [3, p. 10]

The hierarchy that separates teachers from students often acts as a barrier to prevent honest conversation about teaching and learning. Universities have devised many ways to facilitate student feedback to instructors despite this barrier. SGID-based programs are one solution, as are traditional end-of-semester course evaluations.

Course Evaluations vs. Mid-Semester Feedback

Programs like SGID are not teaching evaluations. By design, they fall more into the category of formative evaluation, as opposed to the summative approach of traditional end-of-semester evaluations. Formative assessments are structured to encourage iteration and reflection in a low-stakes environment. Through the SGID process, instructors are encouraged to iterate and test out mid-semester adjustments based on student feedback. Students also give feedback from a formative space – SGID gives them the opportunity to make suggestions that could improve their own learning experience that semester, instead of a summative “review” that won’t impact them at all.

At UAF, participating in Mid-Semester Feedback is entirely voluntary, but instructors can choose to include the MSF report in their tenure and promotion file. Paired with a narrative describing the changes made to the course because of that student feedback, it can serve as an excellent example of how an instructor is using formative assessment to improve teaching.

While outside the scope of this article, significant research has been done on the limitations and biases present in course evaluations [4]. While mid-semester feedback is also subject to many of those biases based on instructor identity and teaching style, it does offer an alternative to some of the sampling bias issues in course evaluations.

One issue with end-of-semester evaluations is recency bias – thoughts on the beginning and middle of the course are often superseded by end-of-semester experiences. An article by Darsie Bowden, a professor of writing at Western Washington University, describes this perspective problem: “Course evaluations by students, even when those students are well intentioned, offer a monologic, more or less rear view mirror reflection of students’ opinions of the course or instructor” [5. p. 2]. The UAF Mid-Semester Feedback program conducts classroom sessions between weeks six and eight of the semester. Those critical first few weeks of class are still fresh in students’ minds!

Student Attitudes towards Submitting Written Course Evaluations

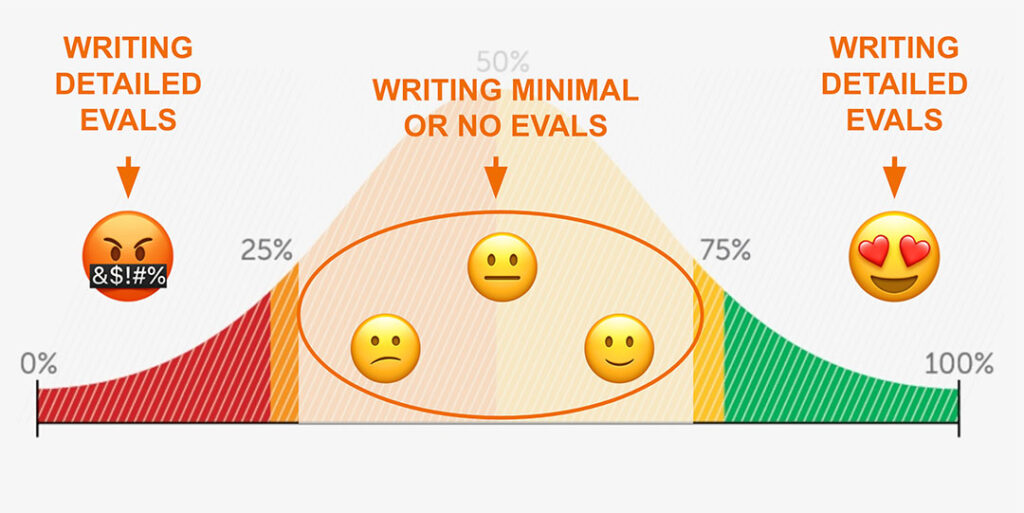

Another way that the UAF Mid-Semester Feedback program can offer an alternate perspective to end-of-semester teaching evaluations is by providing more information on the bell curve of student opinion. Given that end-of-semester evaluations are optional, instructors often find that they get the most feedback from students who have strong opinions about the course, positively or negatively. The Mid-Semester Feedback program actively solicits information from the entire class when it still has a chance to make positive changes in the course. The small group discussions build consensus, as does the final step of voting Yes/No/Neutral on feedback statements. Sometimes students are united in agreement with a suggestion for course improvement, and at other times a split vote can indicate an issue that deserves future discussion to understand more fully. Of course, it’s affirming to see strong consensus on things that are going well!

Impacts of Mid-Semester Feedback

Mid-semester feedback programs provide instructors with feedback that is different from what they receive in end-of-semester evaluations. The question that follows from that is: What are instructors doing with this feedback? How does participating in a SGID-based program influence the classroom environment and student attitudes? Does participation in a SGID-based program impact student learning outcomes in a course?

To be honest, the answer to that last question is: We don’t know yet. Longitudinal, statistically-sound research evaluating the impact of faculty development programming on student success is still an emerging field and studies of that type have not been done on SGID-based programs yet [3, p. 132]. There is a significant body of smaller studies and observational research on the topic though. The enduring popularity of SGID and similar programs over the past 45 years has generated many publications that show that faculty find the program useful, and that they use the feedback to make changes to the course that they perceive as successful [3, p. 90].

Anecdotal feedback from instructors who have participated in the UAF Mid-Semester Feedback program over the past two semesters have also been positive. Instructors often identified one or two pieces of student feedback that could be acted on quickly and easily, and they appreciated the straightforwardness of those insights. They also got confirmation on specific behaviors and policies that students enjoyed and found helpful for their learning, which is great data to have as well.

Many studies have also examined SGID-based programs from a student perspective. Students generally think that mid-semester feedback is more purposeful than end-of-semester feedback, have positive perceptions of the instructor for participating in the program, and see improvement in their own learning and investment in the course [3, p. 85]. Bowden believes that effect on students is the greatest impact of the SGID process:

“The SGID provides a forum to get answers to questions that the teacher and students are afraid to ask. In the process, they discover that these questions are not so “stupid” after all and that the answers to these questions are quite illuminating. Further, it is not just getting answers to questions—the sharing of information—that seems to be important. The opportunity to voice one’s opinions seems to facilitate the process of communication between teacher and student, in and outside of class. The fact that the instructor has been instrumental in providing this forum—that he or she is interested enough in having students’ feedback to set up this experience—gives the students a strong sense that they do indeed have some significant influence on their intellectual growth and development in the class.” [5, p. 9]

Possibilities for Mid-Semester Feedback

The central idea of SGID – facilitating a cycle of conversations among students and instructors about learning – can be adapted to many contexts. Hundreds of universities over the past 45 years have tinkered with the format and application of SGID-based programs. Even within a single university, SGID can be used in multiple ways. A descriptively-titled 1998 article from the University of Michigan, “Using the SGID method for a variety of purposes,” describes the ways SGID has been put to use at their institution [6].

- Mandatory training for new faculty members/TAs with teaching workload

- Department-wide initiative during times of transition or transformation

- Faculty Learning Community in which all participants do a SGID and then discuss the results

- In combination with peer teaching observation for tenure and promotion

- For large courses taught by an instructional team with many sections or labs

I would love to explore the ways our Mid-Semester Feedback program could be adapted to meet the needs of faculty and departments at UAF. If you are interested in using it for a group or specific initiative, please contact me at cfnoomah@alaska.edu.

For instructors who teach in-person, online synchronous, or hybrid courses, program information and registration for Fall 2025 is available on the CTL website at: https://ctl.uaf.edu/2025/02/07/mid-semester-feedback-2025-fall-2025/

References

[1] Clark, D. J., & Redmond, M. V. (1982). Small group instructional diagnosis: Final report. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 217954) https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED217954.pdf

[2] Veeck, A., O’Reilly, K., MacMillan, A., & Yu, H. (2016). The use of collaborative midterm student evaluations to provide actionable results. Journal of Marketing Education, 38(3), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475315619652

[3] Hurney, C.A., Rener, C.M., & Troisi, J.D. (2022). Midcourse Correction for the College Classroom: Putting Small Group Instructional Diagnosis to Work. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003446026

[4] Marsh, H. W., & Roche, L. A. (1997). Making students’ evaluations of teaching effectiveness effective: The critical issues of validity, bias, and utility. American Psychologist, 52(11), 1187–1197. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.11.1187

[5] Bowden, D. (2004). Small Group Instructional Diagnosis: A Method for Enhancing Writing Instruction. WPA: Journal of the Council of Writing Program Administrators, 28(1-2), 115-135.

[6] Black, B. (1998). Using the SGID method for a variety of purposes. In M. Kaplan (Ed.), To Improve the Academy, Vol. 17 (pp. 245-262). http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0017.019