Getting Started with Teaching and Learning Research

What if I told you that you are probably thinking about your teaching problems all wrong?

You’ll know I’m right if you think there is something wrong with having teaching problems. In a bedrock article, Randy Bass (1999) highlights this differing perception of problems:

In scholarship and research, having a ‘problem’ is at the heart of the investigative process; it is the compound of the generative questions around which all creative and productive activity revolves. But in one’s teaching, a ‘problem’ is something you don’t want to have, and if you have one, you probably want to fix it. (p.1)

In other words, teaching problems indicate a space for learning the same way that a research problem does–and we can view that as exciting! And while human mistakes happen in any context–broadly speaking–problems in a teaching practice are no more a personal failing than a problem in a research practice.

But there’s a root for our differing sense of teaching and research problems–for many, teaching just feels so personal. In The Amateaur Hour: A History of College Teaching in America (2020) historian Jonathan Zimmerman explains the conflation between teaching and our personalities has a long precedent. Absent a rigorous standard for teaching equivalent to the peer-review process in research, American academic culture has conflated teaching skill with personality since the early 20th century. As the modern university was developing, the explicit perspective on teaching was that it was a matter of charisma. Popular teachers just had “it” – a personality that could charm students into learning. Unpopular teachers just didn’t (no wonder an unkind student assessment can cause cold sweats).

Takeaways

- American university culture has a long history of erroneously conflating teaching effectiveness and innate personality traits.

- Educational research makes it clear that effective teaching can be learned; the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning extends this, suggesting that researchers from all disciplines can benefit from engaging in research on their own teaching.

- Classroom research can range from informal to formal, publishable studies. Research suggests that this activity improves teaching effectiveness and student outcomes.

Meanwhile, this view of teaching has put college professors in double-bind with their teaching practice. Zimmerman (2020) notes that popularity made an instructor “suspect, precisely because their charisma lacked any real sanction in the scholarly world. Indeed, it could–and often did, count against them” (p. 4). Damned if you have teaching problems; damned if you don’t.

The more salient point is that this fixation on personality has precluded much serious inquiry into teaching practices and assessment from being woven into the fabric of academic life. Drawing again from Zimmerman, “The more Americans saw teaching as a personal act or decision, the less it could be organized or standardized–or improved” (2020, p. 5). While higher education has evolved to include more instructional training, American universities still tend to carry teaching baggage from that era.

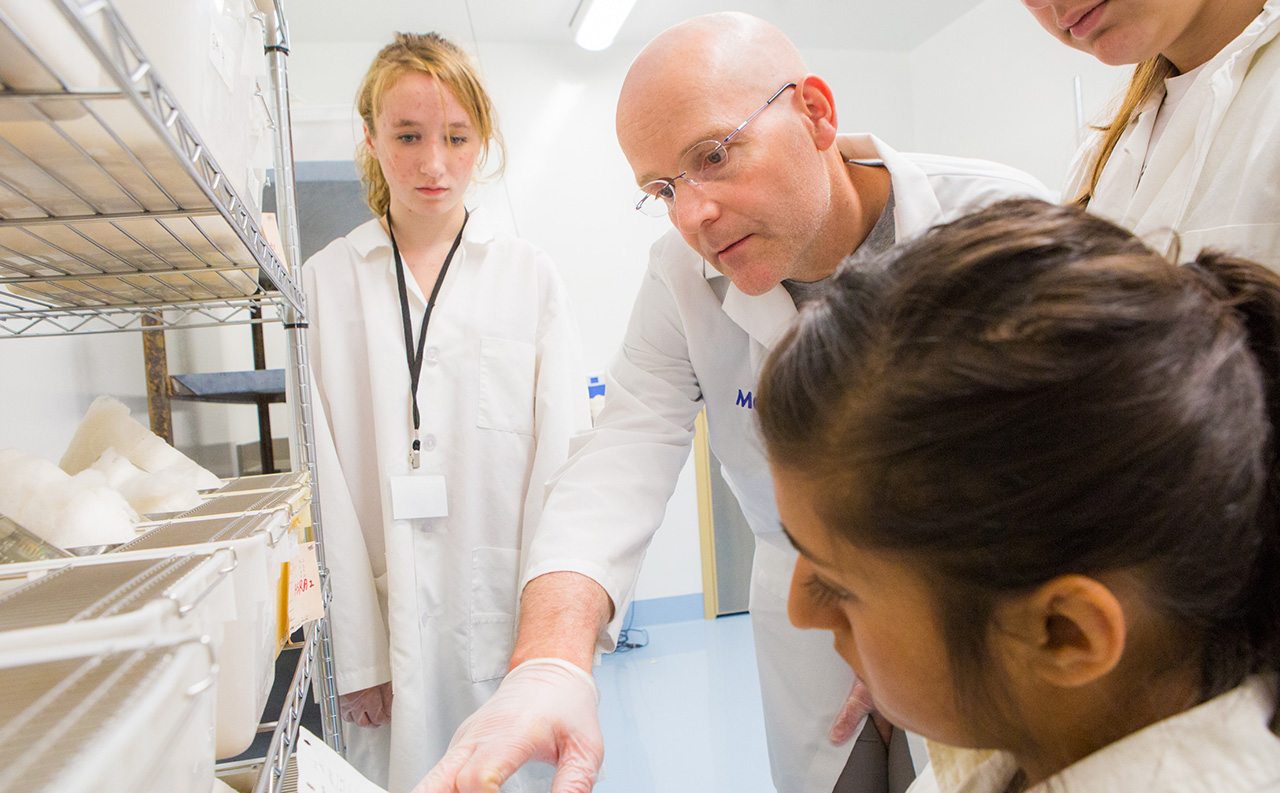

So what can we do in light of this legacy? One answer is to bridge the research and teaching gap in higher education. The field of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, or SOTL, suggests that we can alleviate that burden with tools we already have in academia–research and systematic inquiry. We can look to a robust body of literature to find other people who have encountered the same problems, test their solutions, or innovate our own. Our classes can be our laboratories, our archives, our field research. In other words, we can start getting curious about our teaching problems.

Before we proceed, a caveat on that teaching personality point: just because we can inquire into and improve teaching systematically does not mean that the whole endeavor is mechanistic. Teaching and learning are social–they involve relationships. None of this discounts that sort of “magic” when you and your students just click. Through scholarly teaching, instructors leverage and develop evidence-based practices that work for their own contexts, students, and, yes, personalities. Ultimately, the message of SOTL is: you (no matter who you are) can craft a teaching practice you can be proud of.

SOTL 101

Elon University’s Center for Engaged Learning, a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning hub, defines SOTL as “faculty bringing their habits and skills as scholars to their work as teachers… habits of asking questions, gathering evidence of all different kinds, drawing conclusions or raising new questions, and bringing what they learn through that to… students’ learning” (2013). SOTL researchers aim to highlight the professionalism of teaching in higher education, using the academy’s own language and ways of knowing to acknowledge the difficult work of designing and delivering a course.

SOTL as a distinct field is relatively young, with “Scholarship of Teaching” introduced in 1990; “Learning” was added as the field’s first conferences and journals were established in the early 2000s (Yeo et. al., 2024.). While discussions of the best way to educate are as old as the academy, SOTL is a departure in that it deliberately cuts across disciplines and responds to the teaching challenges of the modern university (Felten & Geertsema, 2023).

The results of a scholarly teaching practice have proven promising. In a review of literature, Felten and Geertsema (2023) report that by participating in SOTL, faculty become more effective teachers and student learning markers also increase. At the same time, scholarly teachers benefit from participating in a community, helping reduce a feeling of isolation common in higher ed teaching.

Felten and Geertsema (2023) also emphasize that engaging in SOTL has impacts beyond the classroom, emphasizing that SOTL work creates space to reflect on our role in the “democratizing mission of higher education” (p. 1097) At its foundation, the field’s mission is to uncover methods for “faculty applying their knowledge and expertise to the pressing needs of society” (p. 1097). SOTL emphasizes effectively welcoming students into our disciplinary methods and expertise to invite more collaborators in addressing social problems.

How to get started

The great thing is that as long as you are teaching, you can practice scholarly teaching. Here are a few things to consider if you are ready to get classroom curious.

Scholarly Teaching or Scholarship of Teaching and Learning? (Yep, it’s either/or.)

SOTL folks tend to distinguish SOTL research from “scholarly teaching” by its intent (Yeo et. al., 2024). Basically, are you planning to contribute to the body of research – i.e. publish– or not? Work meant to be published is SOTL; work that is not is scholarly teaching. Both are worthy endeavors.

If you are only interested in improving your own or an internal process, then you are doing scholarly teaching, and you have a lot of flexibility. Identify a teaching problem you want to dig into. Peruse relevant research, brainstorm with a colleague or Center for Teaching and Learning staff, or attend a training. Then try out an idea you think could improve your practice. Assessment methods could range from comparing student outcomes across semesters, to classroom check-ins, to Canvas surveys.

If you are inclined to publish your findings, then you are SOTL research territory–which means you will need more formal study design. In most cases, you will need to work with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to get your research approved. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods are all common in SOTL literature; while social science methodologies dominate SOTL journals, the field is intentionally inclusive of methods from across disciplines (Felten, 2013).

Review the literature

Researchers at Elon University note that navigating SOTL literature may be an adjustment from your usual disciplinary research. While some disciplines have journals dedicated to their own pedagogical research, not all do. Especially if you work in a very different discipline, it could take some time and patience to find your bearings in the SOTL world. Elon’s Center for Engaged Learning has an excellent roadmap of SOTL research and literature review practices that makes for a helpful starting point.

Include your students

Whether you are doing formal or informal research, when exploring how a teaching practice impacts students it is essential to employ best practices of human research, recognizing the power differentials in a student-teacher relationship, and avoiding a situation where students are objectified in the research process. As a field, SOTL values engaging with students as much as is appropriate, up to co-designing and co-authoring work (Felten, 2013).

Remember it’s an experiment

If you are prone to teaching perfectionism, keep an eye out for it in your teaching research practice. The reality is that if there was an obvious solution, it would not be a problem worth researching. It is possible that your tested intervention will not lead to the results you hope for. If so–well, you’ve found another problem to get curious about. For those of you who have a low risk tolerance for a possibly unsuccessful teaching experiment, know that you can calibrate your research accordingly by implementing small, highly-evidence-based changes. The scholarly practice you bring to your teaching choices will allow you to contextualize and build on any results that do come.

Join a research team!

Interested in some guidance on starting your SOTL journey? The CTL is recruiting for our third SOTL cohort for the upcoming academic year. With a participatory research model, in this program participants refine and contribute to pre-framed research projects. Head here to learn about the upcoming research team.

References

Bass, R. (1999). The Scholarship of Teaching: What’s the problem? Inventio, 1(1), 1–10.

Elon University Center for Engaged Learning. (2013). What is SoTL? https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/studying-engaged-learning/what-is-sotl/

Felten, P. (2013). Principles of good practice in SoTL. Teaching & Learning Inquiry The ISSOTL Journal, 1(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu

Felten, P., & Geertsema, J. (2023). Recovering the heart of SoTL: Inquiring into teaching and learning ‘as if the World Mattered.’ Innovative Higher Education, 48(6), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09675-4

Yeo, M., Miller-Young, J., & Manarin, K. (2023). SoTL Research Methodologies. Routledge.

Zimmerman, J. (2020). The Amateur Hour: A History of College Teaching in America. Johns Hopkins University Press.