Consider Online Teaching Tools to Promote Efficiency and Student Success

During the iconic elevator scene in The Matrix Reloaded, Neo and Morpheus described a dangerously complex environment that their team found themselves in, replete with strange new encrypted code. Trinity asked the definitive question, “Is that good for us, or bad for us?”. Neo then supplied more technical details, “Well, it looks like every floor is wired with explosives”. The details helped Trinity conclude, “Bad for us.”

This teaching tip explores some details to consider when deciding which digital tools to use in your online class such as learning objectives, time, and opportunity. Hopefully you will be empowered to better answer the question, “Good for us, or bad for us” [1].

Faculty have an uncountable number of tools that they may deploy in their online classroom. Instructors are introduced to a whole host of solution providers at conferences, campus workshops and of course, through email. The sheer number of tools can create decision fatigue for faculty, what published studies refer to as “technostress” [2], and “technology fatigue” [3]; for students.

One of the most important course design decisions that instructors can make isn’t finding the right solution, but rather identifying the most pressing challenges. At the end of the semester what really matters is the success of your students, not how many tools were used in the delivery of the course. Before you can determine how to measure that success, you must determine what that success means. This point of where to start designing is a large one and beyond the scope of this teaching tip on the details of tool selection, but you can take a deep dive into the previously posted tips: Backward Design and Big Ideas: Keeping the Expert at the Center.

In one sense, tools, whether they be physical objects like scientific instruments, processes like interlibrary loan requests, or software like video streaming services can be divided into two groups: Content or Support for instruction in the online environment.

If you are providing instruction on the proper use of a mass spectrometer, (something your students will use in the field of Chemistry), or video editing software (to be used in communications and journalism), then that instruction gets tallied as course content. This category of tools and corresponding proficiency of use is usually transferable to other courses in your department’s degree program or the student’s intended vocation. Demonstrating proficient use of these tools is usually part of your course learning objectives.

The other category of tools is used to support learning and assessment in the online realm. In order to even conduct a course online, you and your students will need tools in order to communicate, discuss, demonstrate competency, publish and make assessments. In many cases learning these tools is required to complete an online course, but such learning is not directly part of the knowledge domain that you are trying to impart to your students.

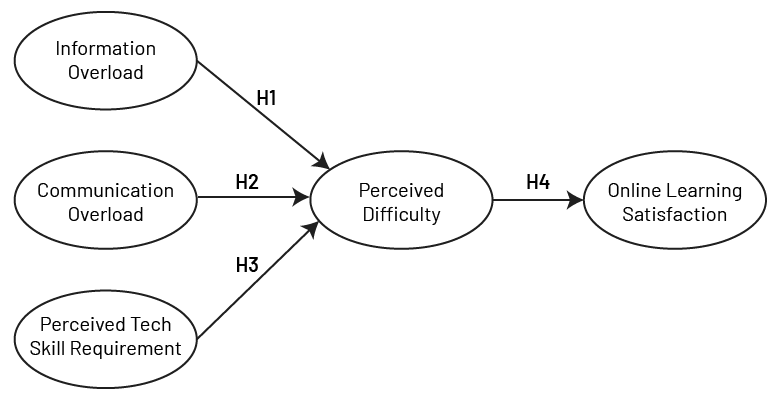

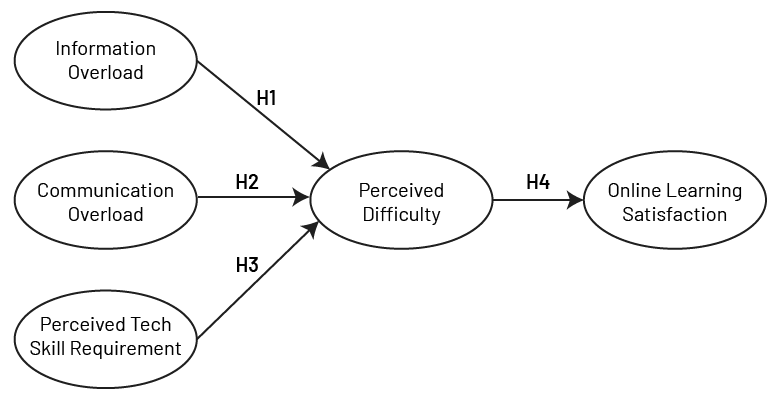

Naturally, in a world where nearly everything is online, the distinction between these categories of tools is often blurred. Students benefit from learning new methods and expanding their skillset, but when too many skills and tool proficiencies are demanded in a single course, your students can suffer the effects of “information and communication overload” [4]. Content has given way to chaos.

Suppose that you are delivering a course next semester and at the end of each of your fourteen weekly units, you direct your students to create, edit, and publish a reflective video. If you make this process consistent, your students only have to learn these skills once, and get better as the semester rolls along. But consider if you decide to have your students publish their videos to different platforms each week. Further, what would happen if you added the requirement to shuffle the task of editing these video reflections between several editing apps?

Unless these varied skills were part of some course studying media, or publishing, you and your students would soon become fatigued from the ever changing requirements of each assignment. The burden of learning new sets of tools would overshadow and undermine the prospects of your students meeting the course’s learning objectives.

Another important factor in tool selection is what kind of support is available for it? Will you have to provide individualized instruction to each student? Will you have to create your own learning materials like a series of annotated screenshots or a screencast? Is there a well supported user community of the tool? Does the publisher have both instructor and student facing manuals available?

Also, and this is another huge teaching tip jumping off point, Is the tool accessible and does it protect student privacy?

In summary you should ask the following questions before considering the use of a tool in your course:

- Does this tool support the course’s instruction, learning activities, or assessments, and help students complete the course learning objectives?

- Can this tool (and corresponding course activity), be repeatedly used throughout the semester, and benefit from the investment of time learning it?

- What instructional content is available for the tool already?

- Is the tool accessible, does it protect student privacy?

Finally, it should be understood that these guidelines have to be applied knowing the context in which it might be used: your classroom. It might be prudent to abandon much of this advice under special circumstances. Consider what you might do with the opportunity of a fantastic guest speaker available for a concurrent session, but they insist on using a communication tool you are not familiar with? If you want your students to chat with that guest speaker, you’ll make an exception and learn a new tool.

You always have the opportunity to experiment and innovate your teaching practices. The instructional design team at UAF’s Center for Teaching and Learning are eager to help you bring your class to the next level. Details about online tools can help you decide when less is more, for success over chaos or the matrix.

References

[1] Wachowski, L. and Wachowski L. (Directors). (2003). The Matrix Reloaded [Film]. Warner Brothers Pictures.

[2] Ayyagari, R., Grover, V., & Purvis, R. (2011). Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. MIS Quarterly, 35(4), 831–858. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409963.

[3] Karr-Wisniewski, P., & Lu, Y. (2010). When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1061–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.008.

[4] Conrad, C., Deng, Q., Caron, I., Shkurska, O., Skerrett, P., & Sundararajan, B. (2022). How student perceptions about online learning difficulty influenced their satisfaction during Canada’s Covid‐19 response. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(3), 534-557.