Sharpening Critical Thought with ChatGPT

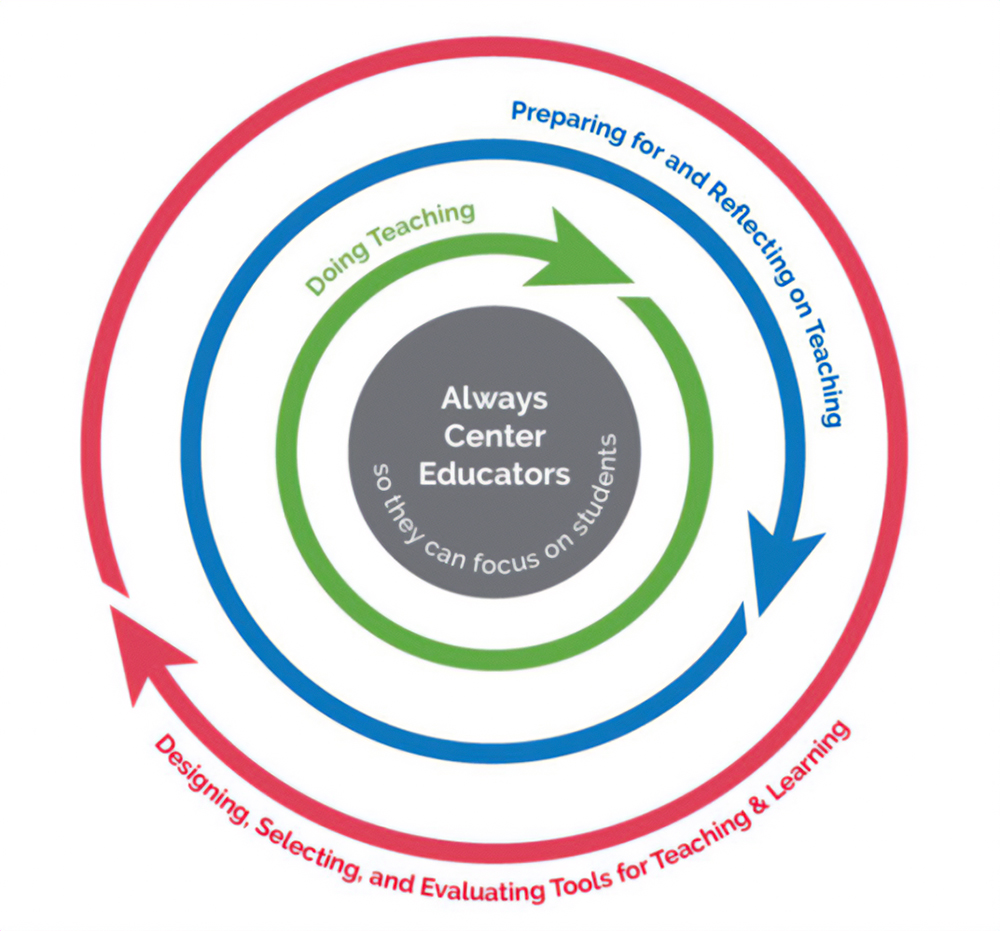

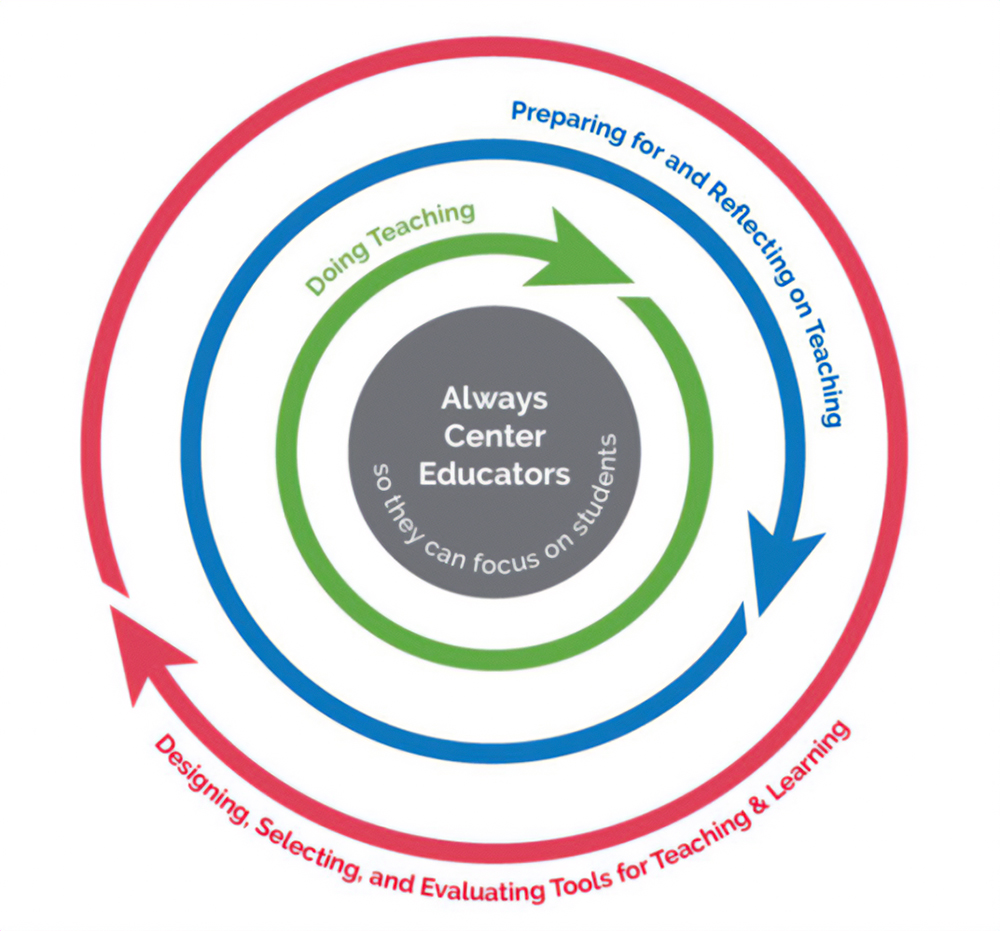

A very recent report from the U.S. Department of Education[1] on Artificial Intelligence lays out some pertinent considerations concerning AIs in instruction. One of the questions is how instructors can and should use AIs to speed up feedback to students, generate practice problems, and help tutor students. In each point of consideration, the report presents a spectrum of possibilities ranging from the instructor doing everything traditionally to the ceding of all decision-making to AIs. The report urges solutions where the educator is kept at the center of design, implementation, and reflection. The report also looks at the possibility of instructors having to spend less time on burdensome activities like reminder emails and announcements so that more time can be freed up and devoted to addressing individual students’ learning misconceptions.

We aren’t the first educators to attempt to teach in a more enriching manner. Sometime back around 2009 two Chemistry instructors, one from Brandeis and the other from the University of Michigan[2], both began employing a new teaching practice in their Organic Chemistry classes. Professors Coppola and Pontrello started giving students answer keys to weekly homework and quiz problems. The twist was that for each problem, the instructors provided two answers. In the keys generated by Coppola and Pontrello, one answer was correct and would receive full credit. The other answer was incorrect in some way. Perhaps it did not contain a complete answer, it may have relied on a false premise or misunderstanding of a key concept, but usually, it had elements of responses that students in the past had typically gotten wrong.

These answer keys were then worked into weekly recitations and small group work. The students were asked to explore each response, one potentially correct and the other less than correct. The students in these low stakes, non-graded recitations were provided the opportunity to test ideas, go back to their texts, ask questions and debate. At first, the chemistry students taking these courses were a bit frustrated at not being provided with correct answers, but after a bit, the students realized that having to analyze and discover the correct choice for themselves not only provided them with the right answer but also a deeper understanding of the material, because they knew why the answer was correct.

So, how can we do this in our courses now, with the least amount of effort and the best results? Let’s use ChatGPT. From previous teaching tips[3], we know that we can use ChatGPT to create questions and exercises for students, and we’ve explored examples of purposefully asking the AI to give us partially false answers. You might consider following an approach as outlined below:

- Generate your own questions, grab similar questions from texts or open sources and ask ChatGPT to produce variations of complexity and particulars to generate a somewhat large question pool.

- Aim at providing two responses, one correct, the other not. Each should provide a result in steps while “showing the work”. Start with your own correct response using material you teach and methods that you approve to develop the correct response. Ask ChatGPT to analyze your correct answer and alter it with common student misconceptions.

- Provide students with this combined “key” of correct and incorrect responses.

- Develop a module-by-module cycle in the course where you cover these questions and responses and have your students go through discovering which is the correct response. Require students to reflect on why the incorrect responses are not true. Did they leave something out? Did they start with an incomplete or false premise? What is missing?

One of the points that Coppola and Pontrello stress in their article was that the students performed well and best used the provided answer keys in a low stakes setting such as a weekly homework/quiz review. You will know what course of action above will work best depending on your subject matter, the maturity of your students, and what your learning objectives are, but this approach should lead you and your students into the practice of employing more critical thought into the learning process.

[1] U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and Future of Teaching and Learning: Insights and Recommendations, Washington, DC. https://tech.ed.gov/ai-future-of-teaching-and-learning/

[2] Coppola, B. P., & Pontrello, J. K. (2014). Using errors to teach through a two-staged, structured review: Peer-reviewed quizzes and “What’s wrong with me?”. Journal of Chemical Education, 91(12), 2148-2154.

[3] https://ctl.uaf.edu/?s=chatgpt